Console

Interview with

Jean Yang

CEO, Akita

A tool for API mapping and observability.

What is Akita? Why did you build it?

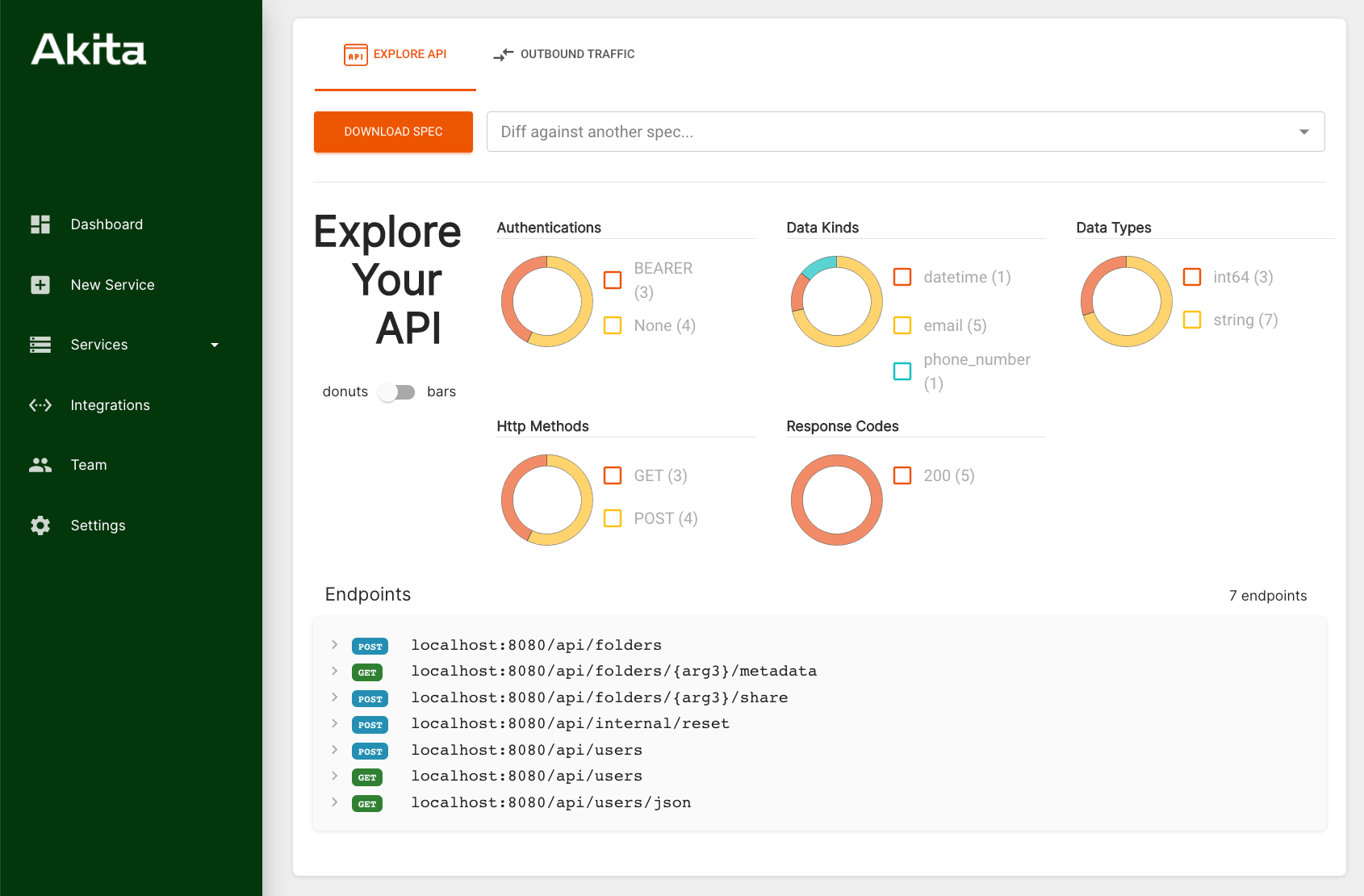

Akita is an API developer tools company. It sits between testing tools and observability tools. We build solutions that watch API traffic and then build models of what's going on with your system. From the models you can generate API specs. You can ask questions, like: "What endpoints do I have?", "What data formats do I have?", "What data types do I have?"

The models also let you track what changed. Instead of diffing source code, you can now diff your API models, which let you talk about things as fine-grained as: "Did I have a change from a US phone number to an international phone number?","Did I change a field name?" In the future, I see us inferring more complex implicit contracts like, did a certain constant value change, or were there relationships between fields that used to exist, but don't exist now?

I realized there was a big gap in where modern tools sit. I was a professor at Carnegie Mellon working on program analysis, static type systems, static verification, and everything at the application level. I realized things were increasingly not at the application level anymore.

For my PhD, I had made a new programming language. I was really excited to try using it, and started building web apps as a prototype. The minute I called out to the database, I was like, “oh no, everything calls out to something else”. As soon as you call out to something else, all of your guarantees within your language or your type system or your analysis, go right out the window.

I had an existential crisis until I realized the API layer was where you could apply many of the ideas developed in programming languages research. You could build up tooling that meets the heterogeneity of software systems. You can fill a real gap where people don’t know what APIs they have or what they do. Ensuring the API behavior doesn’t change is pretty important to keep track of.

Akita API dashboard.

With Akita watching the network traffic, where is it supposed to sit in the stack?

We try to be as non-invasive as possible so there are a couple of different modes. You can run Akita either as an agent - we use pcap filters to passively listen to network traffic. No proxying, no need to intercept any of your traffic. Or, alternatively, we've built the Akita Cloud to operate on HAR files (HTTP archive files). Any way you can generate HAR files, we can consume them - through Chrome’s dev tools, through a proxy, or Akita itself can be set to generate them.

We're also building more and more integrations with frameworks like Django, Flask, FastAPI, Rails and middleware frameworks like Express. We have a daemon mode coming out soon to integrate with different middlewares.

Anywhere where there's traffic, we're trying to have a presence to passively listen to your API calls.

Should Akita run in production or dev?

This is a question I actually didn't really have an answer for yet. The traditional software development life cycle is: you write your code, then you test your code, then you stage your code, then you run it in production.

What we have been finding is that most people write their code, write a few unit tests, then there might be a staging, or it could go straight into production. A lot of the testing happens in production these days, because of all the interactions between the services. One of our goals was to shift things back into tests, but have tests look different. We wanted to shift things back to test a little bit, so Akita can run in CI, and we can then tell people: here's what we saw from watching your behaviors at the test stage.

We also don't disagree that you have to do some of your analysis in production. Most of our users run us right now during CI stage, but we ultimately see ourselves as having a presence everywhere. This will allow us to feed in traffic across environments so you can diff how test differs from production.

We believe watching API traffic is a better way than diffing source code. Right now, there's no unified representation that takes your source code and says, "this is how it relates to your heterogeneous services." We believe API protocols and models are the way to combine those two contexts.

What does a “day-in-the-life” look like?

I don't think there's a typical day-in-the-life. There are a few different prototypes of days and I try to keep them separate. One involves deep-thinking work that needs to be done at this stage of the company. What is our product? How do we tell that story? What needs to be built for that product to work? I try to block off upwards of five hours at a time for thinking like this. When I started out, I ended up doing a lot of this work only at night. The lockdown has made me really come to value blocking five hours in the morning or five hours in the afternoon for this kind of work.

There are other days when there are a lot of meetings. These meetings can take a variety of forms. I try to talk with a lot of developers. Some of them are our users, some of them aren't our users yet. I ask them, "what are your problems?" "What are your workflows?" I try to also workshop, "this is how we're telling our story right now. Is that resonating with you? Which parts? Why not?" Those kinds of questions.

I also spend a lot of time with our team. Planning things and talking about how our next feature should look.

I consider all meetings similar where it's not deep thinking time. I try to keep those days a little bit separate. Then there are periods when other things come up. There are periods of time when we do recruiting, so there are interview days. Or there are days when I try to do a lot of reaching out to our users. There are a lot of different things, but I try to keep the theme of each day not on too many tracks.

What does the team look like?

Right now it's a small team. It's me and a bunch of other escaped academics.

My friend Cole Schlesinger, who got his PhD the same year as me, was one of the earlier people to join me on this endeavor. He was at Amazon AWS before joining Akita, so following his PhD he had spent some years in industry. Initially building compilers and program analyses, but then at AWS he was doing a lot of cloud stuff. It ended up being quite similar to the things I was working on.

Jed Liu, who I had looked up to during my PhD, had been a senior grad student to me and worked on very similar things. I was doing things at the application level, whereas he had been working at the distributed systems level in grad school. I thought this was pretty hardcore - applying guarantees to distributed systems. When that became what we were doing for Akita, I was really delighted to bring him on board.

Mark Gritter found us on the internet. He had started his career on networking work. One of our investors actually had looked up to Mark when our investor was a PhD student at Stanford. Mark had written this early Internet architecture paper with David Cheriton, who's one of the big computer networking guys. Mark had gone on to co-found a company in distributed storage. He got interested in observability, then got interested in developer tools from his work in observability correctness. There really isn't too much that's explicitly in the intersection of observability and correctness right now. It was a really good fit.

How did you first get into software development?

Both my parents were computer scientists. They were electrical engineers before computer science was a discipline. They both taught at university in China and got into computer science because they saw it was up and coming.

We had a terminal in our house when I was really little, then we got our first computer which was the Gateway 2000. It's no Commodore64, but it's up there. My parents really valued teaching me things. They made me learn Basic.

My school also taught us Logo with the turtle. We used to go down into the basement room with our floppy disks. This was very progressive for a school in the early nineties. I just thought it was super fun. I didn't have any siblings when I was really little - my sister's much younger. There's not much to do if you don't have siblings so I’d find myself writing little programs on the computer or playing computer games. This was before the internet, so programs were the only way to create infinite entertainment for yourself.

I was obsessed with the web, and I think that that was a big part of why I got really interested in making web programming better. In the early to mid-nineties, I got an email address. I got on the Internet. There weren't very many webpages then! I remember I used to do my daily crawl of all search engines to see what new websites showed up on the internet. I just thought the connectivity of the internet was so fun. I remember I had a Tamagotchi website, and I used to hang out in these Tamagotchi chat rooms. I was really into that.

What languages did you learn?

HTML and Javascript were first. It's not something that a lot of people admit as a big starting language from that era! I also spent a lot of time in C, C++ and Java. That's what we learned in school at the time. In college, I got introduced to the ML family. First OCaml, then I taught myself Haskell. I did my senior thesis on Haskell.

In grad school, I spent a lot of time with strongly-typed functional languages until I realized I was one of the few grad students at MIT that was working in them. I was working in OCaml, then I worked in Haskell, then I worked in Scala for a while, because this was a compromise. Finally, I went back to Python. I think that the smarmy way to say it is, I decided I didn't need types anymore. I was a good enough programmer, and threw away the seatbelt. I thought this would make me go faster, but it was really that the libraries and the peer support was better. I had more friends programming in Python around me at the time.

Is that what Akita is written in primarily?

I don't do the primary development on Akita. I let the team choose the languages. It used to be primarily Go and now it's coded in Python, Go and TypeScript.

What has been the most interesting challenge building Akita?

The challenge has always been defining the problem. We knew we wanted to build a better way of automatically understanding API behaviors, but at first we weren’t sure how. We came upon building Akita by starting out developing an API fuzzer. In the beginning, we were trying to track data flows, as that was my research at the time. We needed to do it in an opaque way because people said they didn't really want to install this across every service of their entire system just to watch API traffic. That created a set of tactical challenges. In order to understand data flows, you need to be at your points of ingress.

The only way we could think to do that was fuzzing. Even with the fuzzer, we had to come up with ways to insert into systems in a very lightweight way. Initially it was Docker. We considered, "how do we finagle the system to watch things passively?" We then came up with a set of tactical challenges, which is, "how do we know what the APIs are to fuzz?" We realized people didn’t actually know themselves, so we had to learn how to get those APIs in a non-invasive way. Some of the challenges were figuring out how to use a pcap filter, figuring out how to use Go packets, figuring out how to use tcpdump with Docker.

"How do we get clean, precise API specifications out of traces?" is another big challenge. That's where my research background comes in because much of the work I did was about getting structure out of something completely unstructured. When you're looking at API traffic, there's a lot of messy stuff in there. There are timestamps, there might be many different values, but the fact that they're different is not always relevant. For example, understanding whether fields are all one type, or whether there is a particular property that always has a certain value, is an enum, or is between a particular range. It's not simply a matter of switching on something like supervised learning, a neural net or clustering and expecting it to do the trick.

I'm really glad that Mark and other people on the team have that systems experience. This is very much a compilers and programming languages problem.

How does the comparison work?

It is a simple diff but it depends on the precision of the model. For example if you're just diffing on a user ID field value it's not that much better than diffing on the source code. If you can infer that it’s a user ID, that makes a big difference. This helps us understand what valid values are, rather than just showing that something changed.

If you can abstract away the details that don't matter, our belief is your diffs can be a lot cleaner, and this starts giving you a way to capture time series information in a non-overwhelming way.

What's the most interesting tech you're playing around with at the moment?

We recently hooked into testing frameworks to get at their API traffic. Most of the time people think of integrations like this as a boring thing, but having built my own programming language as part of my PhD, figuring out the cleanest way to integrate into various frameworks has been really interesting.

When we integrated with Django, Flask and FastAPI, we replaced their test client with ours. We figure out how they're intercepting requests, or how they're handling requests and responses. Everything that gets handled by the test client, we add something that writes things to HAR files. For the developer this means it’s just a one-line code replacement to funnel stuff off to us now.

We found the same thing recently for the Rails middleware. We found that there's a way that you can add a listener to Ruby Controller where you can inject what you need in a very lightweight way.

What I've delighted in my work is finding very clean insertions into systems that are often quite technical. To get in there so the developer has to do as little work as possible. We spend a lot of time thinking about the developer experience so that it really is just a few lines of code to integrate and get your data into Akita. We've been playing with a lot of frameworks to try to figure that out. Whatever we create a really lightweight way to do it, I'm always really excited.

Describe your computer hardware setup

I use a Mac. I switched in 2017. I was proudly one of my last friends I knew to dual boot Windows and Linux. I don't know if you have ever done a Windows Linux dual boot, but over time you’ve had to start switching off more and more stuff in the BIOS. It was never clear how to do it anymore.

The transition started after I took my professor job because I started to do less coding. As a grad student I was mostly on Linux, only going to Windows when I had to make talks. As a professor, I was mostly spending time writing talks, so I ended up on Windows more and more.

There's also a bunch of software that wasn't really well supported on Linux, like Dropbox. When you start doing a lot of talks, Dropbox becomes a much better file management system then just SVN on AFS, which is what I was using. I was also doing a lot of Skype at the time because Zoom was not hip yet among academics. I switched to Mac in large part because I felt it had a more integrated terminal. I still don't use the terminals as much as I'd like, but I've liked it more than the Linux / Windows dual boot.

Describe your computer software setup

OS: macOS.

Browser: Chrome.

Email: Gmail.

Chat: Slack. A lot of my chat that used to be on Gchat or Facebook Messenger now happens on Signal or WhatsApp these days.

IDE: Vim.

Source control: GitHub.

Describe your desk setup

My boyfriend is a graphics professor so I recently switched to his spare high-resolution monitor. I really didn't want to switch because he said, "once you switch, you can never go back." I said, "yeah, that's the point. I don't want to be ruined."

Now when anybody sends me screenshots that they've taken on their monitor, the screenshots look blurry to me, which I hate. Even screenshots our designers took, I'm like, "yep. I can see more pixels than you have." And so I guess that's the fancy part of my setup.

I do have some stuff that I use for live streaming, but I don't use it very much. I have a standalone mic. I really don't turn it on that much unless I'm live recording because you have to be a certain distance from the mic, which is a bit of a pain. I don't have a ring light, but I have some positioned lights. If I'm giving a talk, I'll try to balance the light off my face a little bit by bouncing the lights off the wall.

I read that standing desks are just as bad as sitting the whole time, so, I try to walk around every couple hours or so. I had built myself a standing desk out of old computers when I was a grad student, but it was very tiring for me to stand all day. That's the real reason I don't have one. I can't stand and focus at the same time.

When coding

Daytime or nighttime? Nightime.

Tea or coffee? I actually gave up both, but I was a coffee person.

Silence or music? Music.

What non-tech activities do you like to do?

Most of my hobbies also involve the computer, but I developed a matchmaking hobby over lockdown. On jeandate.com, I started matchmaking my friends, and then that led to producing two shows: Zoom Bachelorette and Zoom Bachelor that were the Zoom versions of ABC's The Bachelorette and The Bachelor. That was fun to do. We got covered by Forbes and CNN.

Find out more

Akita is a tool for API mapping and observability. The beta release was featured in the Console newsletter on 29 Apr 2021. This interview was conducted on 21 Apr 2021.

Subscribe to the weekly Console newsletter

An email digest of the best tools and beta releases for developers. Every Thursday. See the latest email